They kind of stuck it to him again just a block away from his grave when this happened

GENERAL NATHANIEL WOODHULL

GENERAL NATHANIEL WOODHULL

1722-1776

“I get no respect….no respect at all”

The signature is genuine, the face however belongs to the late Joel Cohen of Richmond Hill, Queens. I would of posted a real portrait of the first General to die in the Revolutionary War if I could find one…..It seems other generals and colonels on both sides of the war all have portraits plastered here and there except for Nat. For many years since I first learned and gathered few things about Nathaniel Woodhull, I have somehow always thought of what happened to him when he was alive, the manner in which he died and the disposal of his property after he died, in the light of Joel Cohen’s signature line he would utter from the stage for years on end under the name of Rodney Dangerfield. “I get no respect….no respect at all.” And that’s just the way it appears to me when it comes to the Nat Woodhull story … BTW Only his close friends called him Nat ! and Joel was born in 1921 in Jamaica, Queens … where Nat met his fate 145 years earlier. So with that disclaimer, greetings pilgrim…..and feel free to read on

First A Little History

FROM NEWSDAY’s “LI OUR STORY” WEBSITE

A Hero’s Last Words

‘God save us all,’ Nathaniel Woodhull told his attackers … Or did he?

By George DeWan Newsday Staff Writer

Schools are named for him, an honor reserved for heroes. Textbooks cite him as a model of patriotism during the Revolutionary War. Every Memorial Day, the American Legion stops at his gravesite in Mastic to pay him respect. There is an often-told legend of his bravery in the face of death. When ordered by his British captors to say “God save the king!” Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Woodhull of Mastic replied defiantly, “God save us all!” At this, a furious British cavalryman slashed Woodhull with his saber, and the Long Island general died within days. The tale of Woodhull’s death has been boiled down to these four words: “God save us all!”

But he probably never uttered them.

Was Nathaniel Woodhull the Island’s greatest revolutionary hero, whose ringing words of defiance as he faced death made him a martyr to the cause of liberty? Or are the stories of a soldier’s final and agonizing days colored by the myth-making of hero-worshiping historians and journalists? Woodhull was born of a well-to-do landholding family at Mastic on Dec. 30, 1722. He later married his neighbor, Ruth Floyd, sister of William Floyd, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. When he was 36, Woodhull joined the New York provincial forces as a major, to fight for the British in the French and Indian War. In August, 1775, on the eve of the Revolution, he was elected to the prestigious position of president of the New York Provincial Congress, the illegal Patriot governing body, which, in turn, appointed him head of the combined militias of Suffolk and Queens Counties.

On the eve of the Battle of Long Island — in August, 1776 — Woodhull went to war. But surprisingly, given his rank and stature, he was not sent to Brooklyn to defend against the British. Instead, he was ordered to put on his general’s uniform and become a cattle herder. Ever the dutiful soldier, he complied. Not that the assignment was unimportant. There were 100,000 head of cattle spread across Long Island from Queens to Montauk. In addition to the Island’s prolific agricultural resources, these stock were crucial to the British as a source of food for their armies. Woodhull’s orders were to drive the cattle east to keep them out of the hands of the enemy. His problem was that he had only 190 militiamen to do the job, and he never knew on falling asleep at night how many of them would still be around by morning.

The next stage of the Woodhull story — in fact, the final stage of his life — has taken on mythic proportions.

Records of the Provincial Congress show that late on Aug. 27, with only about 90 men remaining — and they were fast deserting — Woodhull’s troops had driven 1,400 cattle out onto the Hempstead Plains and had 300 more ready to go. A severe thunderstorm drove the general to take refuge in a tavern run by Increase Carpenter, about two miles east of Jamaica in what is now Hollis. In a forlorn letter earlier in the day, Woodhull begged the Congress (now called the Convention of the People of the State of New York), for more troops. The next day, he wrote again:

If you cannot send me an immediate reinforcement, I am afraid I shall have no men with me by tomorrow night, for they consider themselves in an enemy’s country . . . I hope the Convention does not expect me to make bricks without straw.

It was the last letter Woodhull would write. A few hours later, a British cavalry patrol surrounded the tavern, and Woodhull was captured and mortally wounded. What exactly happened at Increase Carpenter’s tavern is not certain, but the “God save the king” version of the story has been told time and again.

It was not until Feb. 28, 1821 — almost 45 years after the fact — that Woodhull the Martyred Hero was created. On that day, an anonymous ballad about the heroic death of Nathaniel Woodhull appeared in the National Advocate newspaper in New York. The ballad included the line “God save us all!” Though there is no evidence to support the story, it has been told to schoolchildren — and countless adults — for years. Without regular repetition, such historical anecdotes have little staying power. In this case, Woodhull — who certainly had a splendid record up to that point — has had his name burnished by some of Long Island’s best-known historians. Silas Wood, the Island’s first historian, repeated the story in his 1826 history. A few years later, Benjamin F. Thompson, repeated the Silas Wood story almost word for word. Since then, popular histories have continued the “God save the king!” story — including three that are currently used with students either in grade four or in junior high school.

There have been plenty of skeptics, nonetheless. For example, in 1902, historian Peter Ross called the Silas Wood narrative of Woodhull’s capture “one of the wonder tales with which the details of the incidents of every war are embellished.” Another historian, *W.H. Sabine, later wrote, “Someone had transformed the once unresisting victim into a martyred hero.” But there is no question that Woodhull was severely wounded by sword in the head and arm in the course of being captured. Some sources say he was caught trying to escape over a wooden fence. Others say he manfully and patriotically stood his ground, offered his sword in surrender — a common and honorable practice at the time — only to be brutally hacked at by British soldiers.

Woodhull was taken to Jamaica, where the wounds were dressed by a British surgeon, then, with other prisoners, moved to Gravesend and put on board a filthy prison ship in the harbor. Later he was taken to a house-hospital in New Utrecht. His gangrenous arm had to be amputated. It was too late. Nathaniel Woodhull died on Sept. 20, 1776, at age 54. He was buried at his Mastic home. But the legend lives on.

I am in the process of obtaining several of William Henry Waldo Sabine’s books on Woodhull “Suppressed history of General Nathaniel Woodhull”, “Murder, 1776, & Washington’s policy of silence “ and perhaps the one closest to the source from neighbor and in law “The Historical Memoirs of William Smith 1778-1783”

The only painting I could find of Nathaniel Woodhull is this one in the Nassau County Museum.

An artists recreation of his darkest day in Hollis, Queens probably painted a hundred years after the fact.

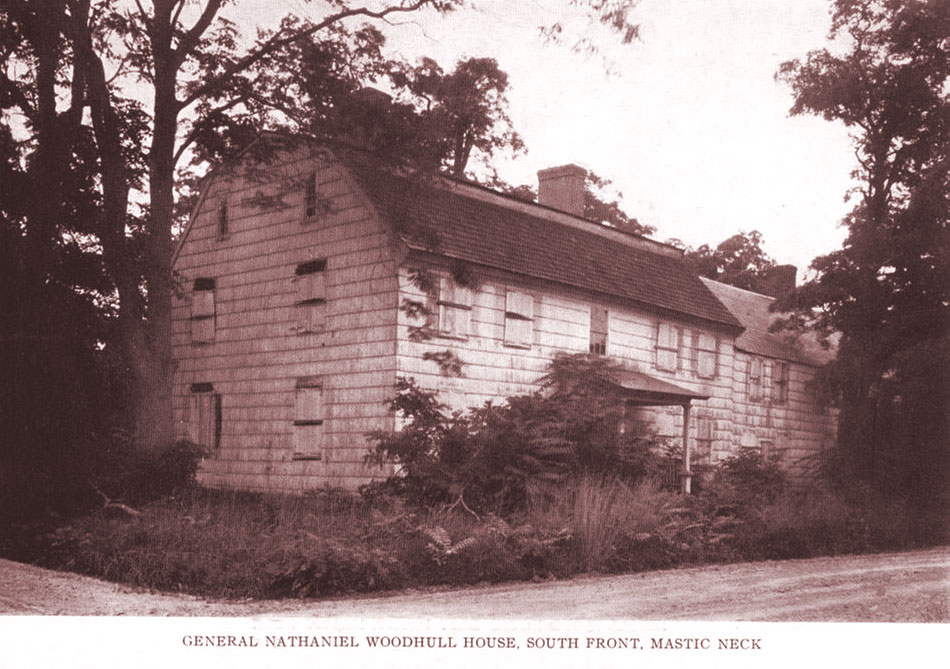

FAST FORWARD 150 YEARS TO 1926

When the Smadbeck Brothers (Home Guardian Company) bought the Lawrence estate in the winter of 1926 to begin the development of Mastic Beach, Nat’s house was included with deal, It was probably vacant for a long time and they may of thought of it as a door prize. I believe there was a fire in it at one time? By the fall of that year the Smadbeck’s offered it gratis to the Colonial Dames of America and a Pear Tree from Corn Court to the D.A.R. Daughters Of American Revolution …they also were more than willing to throw in the nearby graveyard.

The Dames may have taken them up on the graveyard but looks like they took a pass on the homestead. For in Septermber of 1927 this ad appeared in The New York Times. As far as I know it ran for just one weekend.

Very Reasonable or not I don’t think the Smadbecks ever unloaded it. From there on it just fell into worse disrepair according to the few locals like Mrs. Schulz who still remember it. Then in the spring of 1938……… while honoring the General on May 30 with a parade and the First Graveside Memorial Day Service

HEADING EAST TO SEE THE GENERAL

MASTIC – The police were called Monday morning by someone who reported the old Woodhull mansion was being robbed of lumber. Officers Oakley and Waldron found a truck being loaded at the place, but learned that the lumber had been bought and would be used for an antique style house in Southampton Moriches Tribune Friday June 3,1938

Now this is just a theory based on the few facts I know about who was tearing Nat’s House Down. In an interview I did with Estelle Schulz in 2001 she told me it was none other than Willie Schluder who dismantled the Woodhull place. Now couple that with the fact that Willie was in the employ of J F “Dodi” Knapp at that time and that J F had just sold a bunch of his estate off to Smadbecks…how much of a stretch would it be to think that it was old Dodi who got first shot at the lumber in Woodhull’s place? Also we know Dodi’s sister had a place in Southampton Town and he would soon follow her out there in Hampton Bays…… so did the wood from Woodhull wind up in a Hampton Knapp house or barn or kennel? Pardon the pun but it “would” not be a surprise to me. Who WOOD of Thunk It?

ONCE UPON A TIME IN MASTIC NECK ON CORN COURT

His brother in law William Floyd lived about a mile to the east just across Odell’s Creek

Circa 1910-11 Nobody’s Home …..

CORN COURT, MASTIC BEACH, NY AUGUST 2004

Two Hundred and Twenty Eight Years After The General Left Home To Herd Cows For General Washington

A FEW WORDS FROM A MEMBER OF FAMILY

When 76-year-old Edward H.L. Smith of Nissequogue wanted to join the Sons of the Revolution years ago, he had to come up with an ancestor who had fought in the Revolutionary War. For him, it was easy, since Nathaniel Woodhull was his great-great-great-great grandfather. “It’s interesting, but by the time you go back eight or ten generations, you have all kinds of ancestors,” says Smith, who worked for both the state and Suffolk County governments and twice ran for Smithtown supervisor. “Some of them do good, some are just ordinary people. I don’t think it makes too much of an impression on people to have someone like this as an ancestor.” … Newsday

SEPTEMBER 2001

Although you can no longer read the stone the epitah said:

“regretted by all who knew how to value his many private virtues and that pure zeal for the rights of his Country to which he perished a victim”

MRS. ELIZABETH SMITH, WHO MARRIED INTO THE TANGIER SMITH FAMILY

WAS THE GENERAL’s DAUGHTER. THE CITY OF NEW YORK PRESENTED HER WITH THIS SCRAPBOOK ON HER FATHER IN 1825.